The voyages of Māori and Polynesian ancestors across vast oceans were “at the cutting edge of knowledge”, says a University of Waikato researcher.

Dr Haki Tuaupiki is researching traditional ocean navigation in te reo Māori.

Dr Haki Tuaupiki from the Faculty of Māori and Indigenous Studies is two years into a three-year Marsden Fund Fast-Start Grant research project looking into ancestral seafaring knowledge of tūpuna Māori (ancestors).

He is analysing traditional narratives, including waiata (song), karakia (prayers), mōteatea (chants), whakataukī (proverbs) and pūrākau (ancient narratives) as part of in-depth literature review to understand more about these master seafarers.

The journey of ancient Māori from Hawaiki to Aotearoa is, according to some scholars, “the greatest sea expedition and feat of all time”, says Dr Tuaupiki.

“The prowess and understanding of the Polynesian, Micronesian and Melanesian navigators to plan return voyages right across Te Moana Nui A Kiwa (Pacific Ocean). When the Spanish [navigators] and Vikings were hugging the shores, centuries before that Polynesians were crossing the Pacific Ocean.”

Dr Tuaupiki’s research into ancient stories reveals the skill of Polynesian seafarers, who observed their natural environment and drew on traditional knowledge passed down across the generations to plan epic sea journeys on large double-hulled voyaging waka (canoes).

Observing the stars and nature helped tūpuna plan long sea voyages.

“They must have been some of the best marine scientists, astronomers, meteorologists, and boat building engineers to plan these voyages and build these vessels.”

Dr Tuaupiki is currently collaborating with the Ministry of Education to develop a te reo Māori app for Year 6-8 students on aspects of traditional navigation. The app will include a talking avatar feature that will have interactive games and puzzles. There will be aspects of a digital story book with puzzles, tasks and activities throughout. It is hoped that this work will contribute to the New Zealand school STEM and science curriculum, launching in mid-2022.

His research reveals that tūpuna considered a variety of environmental factors – including the sun and stars, the movement of wind and clouds, ocean currents, and bird and whale migration, and seasonal patterns - when choosing when to sail long distances.

“What really blows me away is that our ancestors had an intimate understanding of their environment, and when to make long-distance voyages. They understood the weather, climate and seasons.”

Knowledge of the Pacific cyclone season was vital when choosing a favourable travel window for voyaging, says Dr Tuaupiki.

“According to our traditions, November to March must have been a favorable window to voyage from Hawaiki to Aotearoa, because that is the cyclone season. They used that particular weather pattern to voyage south.”

The flight patterns of certain birds - such as the kuaka (bar-tailed godwit) and pīpīwharauroa (shining cuckoo) - were also a sign that winds were favourable to make long journeys south.

The godwit makes its annual migration from Russia and Alaska through the Pacific down to New Zealand during the Pacific cyclone season, and the shining cuckoo also journeys south from the Pacific to Aotearoa around that time. The migration of whales to Antarctica - often vast in number in ancient times - was also a sign that it was a favourable time for seafaring across the ocean.

Ocean birds take flight.

“Ancestors understood the movement of nature,” says Dr Tuaupiki. “This is all backed up with traditional narratives and published scholarly research.”

Stories passed down about the journey of the Tainui voyaging canoe also indicate that it arrived in New Zealand during the Pacific Cyclone season of November to March.

“Traditions talk about the ancestors seeing all these red blooms when they made their way into Cape Runaway - Whangaparāoa - on the east coast just south of Whakatāne,” says Dr Tuaupiki. “During summer, you see the pōhutukawa blooming right along that coast. Traditional narratives match up with the timing of when Tainui waka arrived in Aotearoa.”

He says the voyaging canoes built by tūpuna Māori were robust and well-built. Some of the double-hulled canoes were up to 80 feet long, with sails and rigs, with single or double masts. There was space to store food and resources, and the larger waka accommodated up to 30 people.

Uncovering the ancestral stories was challenging, says Dr Tuaupiki. Much of the knowledge was scattered across different books, journal articles, papers and audio recordings.

“I’ve found that our waiata - our songs - have been a treasure trove [of information],” says Dr Tuaupiki.

He acknowledges the work of others who had collected and published waiata in books in the 1960s, 70s and 80s, including Te Rangikāheke, Āpirana Ngata, Bruce Biggs and Margaret Orbell.

As a fluent speaker and scholar of te reo Māori, Dr Tuaupiki had the depth of knowledge and understanding to “look in the window” and interpret the stories behind proverbs and waiata.

Dr Tuaupiki has collaborated with other navigators from Hawai'i and across Polynesia.

Dr Tuaupiki has worked closely with Tauranga-based Māori master navigator Jack Thatcher to understand what was revealed in the literature review.

“Jack is the most senior contemporary navigator in Aotearoa, and he studied under expert Hawaiian navigator, Nainoa Thomson who trained under Mau Piailug, from Micronesia, instrumental in reviving Polynesian navigation across the Pacific.”

The Polynesian revitalisation of ancestral navigation began in the 1970s, explains Dr Tuaupiki, led by a group of Hawaiians, who were guided by Piailug, In 1976, together they built a double-hulled voyaging canoe, Hōkūleʻa, and travelled from Hawaii to Tahiti.

“From 1976 until this day, Polynesian long distance navigation has grown, and it all started with that one Micronesian man showing the Hawaiians how to do it.”

Contributing to the revitalisation of traditional voyaging has been a positive outcome of the research, along with communicating it to Māori communities at tribal hui (meetings) and on marae.

“There is value in understanding this knowledge of our ancestors, and there is a strong appetite among Māori communities, schools, high schools, universities and tertiary institutions, and among students studying the reo, to learn more about their ancestors in their ancestral tongue,” says Dr Tuaupiki, who affiliates to Waikato and Ngāti Tuwharetoa iwi.

Sharing research with whānau and communities at wānanga and hui helps break down the barriers between academia and Māori communities.

“It’s important to be “kanohi kitea” - the seen face [in Māori culture]. It’s someone who regularly attends hui face-to-face, who is involved, not just in the library or in their office.

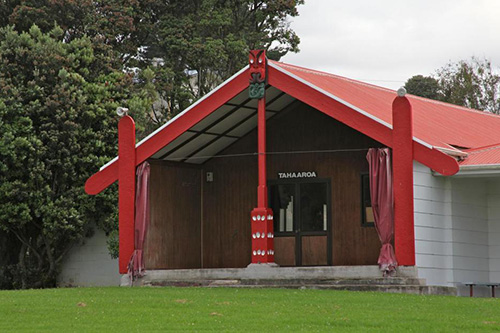

“Māori communities really respect people that “do the doing”, that turn up. It’s an important value. I express my values by turning up and sharing my knowledge, face-to-face. I love sharing knowledge in these beautifully carved meeting houses, nestled in the marae, in front of the carvings that depict our ancestors, their stories, battles, journeys,” says Dr Tuaupiki.

Sharing his research with his community is important to Dr Tuaupiki. Pictured is Āruka marae at Tahaaroa, where he grew up.

Dr Tuaupiki has always had a love of the ocean, so his research has been a personal calling.

“I was brought up on and in and around the ocean in a small community called Tahaaroa on the west coast [of the North Island] south of Kāwhia.”

As a child, the ocean was seen as a precious resource, a place not so much for play but where he and his siblings helped his parents harvest kaimoana, “fishing, diving, collecting shellfish”, and that food was shared with relatives.

He was first introduced to waka ama (outrigger canoeing) by his early mentor Hotu Kerr. Over the next two decades, this passion developed to include an interest in waka taua ceremonial Māori war canoes - and involvement in the annual Kīngitanga regatta at Ngāruawāhia.

In 2002, he spent four months living in Hawaii, learning how to sail on the Hawaiian voyaging canoe, Makali’i, and being on the water in a waka is something he enjoys to this day.

“Being introduced to waka ama 22 years ago, and consequently involved in the sailing community and having the opportunity to go to Hawaii, the passion has evolved for the art, the knowledge and practice. At the heart of it, for me, is learning more about the ancient knowledge of our ancestors in the language of our ancestors.”

In 2020, Dr Tuaupiki was awarded the Fulbright Ngā Pae o te Māramatanga Scholar Award.

Covid-19 travel restrictions have so far stymied his plans to travel to Hawaii as planned for the Fulbright, and to complete the final part of his Marsden-funded project - a waka journey from New Zealand to Hawaii “to test out some of the practice and the theory”.

However, his work home in New Zealand continues, and will impact the next generation of te reo Māori speaking scientists, astronomers and seafarers.